Overview of previous posts here

Towards the end of the network

The industry kept working with economists throughout the 1990's. The same activities as explored iextensively in previous blogposts continued: attending conferences, writing op-eds, appearing at testimony, etc. As there's not much new too learn, I will not go into detail.

Until roughly 1992 the LTDL documents many activities. After that, it becomes increasingly difficult to find anything substantial, and many network members suddenly disappeared from the files. One is money (we'll another reason at the end of this post)

In 1991 the Tobacco Institute faced a

budget cut of 1.1 million US$, so one reason is the institute had to downsize certain activities:

(...)

The summary of a June 26, 1991 meeting are revealing the industry

did not just improvise and the "

that the heart

of the current program is the consulting economists who produce the

studies, get them published and promote them in academic circles"

(...)

The same document shows that year the industry had already spent $16,290 and only had a budget of $19,710 left. In the late 1980's the industry had paid the tobacco economists $15,500 to appear at one convention, so the 1992 budget in comparison was minimal.

Further, around that time, the Tobacco Institute wrote many memoranda complaining about 'going over budget' (not just for the social cost economists), showing the budget cut must have really hurt the Institute. From 1985 to 1991 the economists appeared at economic conferences, but not afterwards.

Many of the original members were dropped around 1991/1992, leaving only an ever smaller core group. The "tax hearing witnesses" list was decreased from an economist in every state to

just three economists: Robert D. Tollison, Richard A. Wagner and Dwight R. Lee

In 1993, the Tobacco Institute still suffered from the decreased budget, leading to the Tobacco Institute

demanding a new contract with James Savarese

Even though the network kept delivering material until at least 1998, this letter probably marked the final turning point in the functioning of the network. The letter to Savarese was written on the same day as a document announcing

the Tobacco Institute's 1994 budget would decrease another 62%

Some members of the network started working for the individual tobacco companies, such as Philip Morris (e.g. Walter E. Williams), R. J. Reynolds (Richard Wagner, from 1994). Tollison on his side started working for British American Tobacco in 1993. The economists may have been

too expensive for the reduced budget

Still, in 1994 the Tobacco Institute

budgeted $102,000 - $194,000 for the activities of Tollison, Wagner and Lee

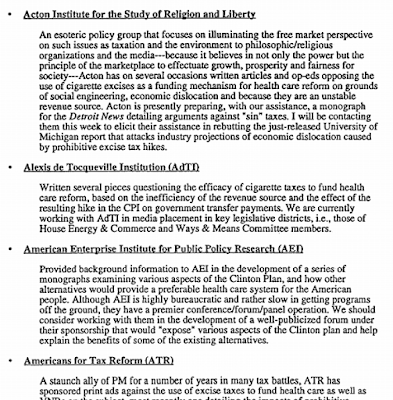

From about 1993, the industry shifted to using think tanks (especially the

Independent Institute - this will be explored in future blogposts) instead of directly ordering reports from the economists. But it was not the end of the network yet, as the economists still wrote op-eds, and Tollison and Lee still appeared at hearings.

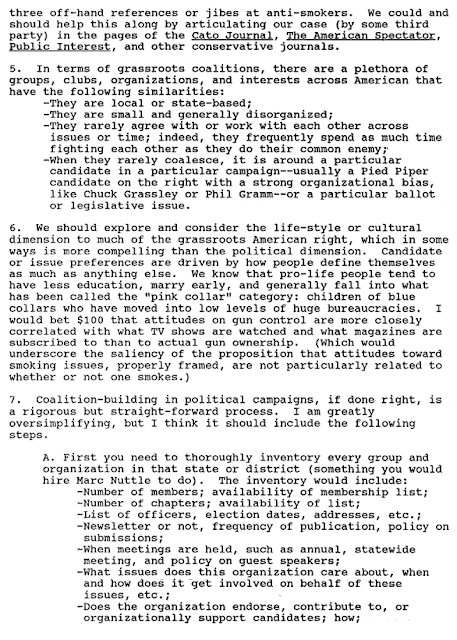

The Tobacco Institute sent a memo in 1995 mentioning that the

economic consultants still were able to provide op-eds in no less than 30 states and effectively the economists started organizing an op-ed campaign against FDA-regulations, with

17 economists trying to get published, including a new names (Lowell Gallaway). The industry once again pressed its agenda, and suggested to write on

In 1996, not 17 but

20 op-eds were sent to newspapers. In 1998 the last new name that could be found appears:

Gary D. Ferrier wrote an op-ed that year, but there is no indication he ever was formally recruited. His name appears in exactly five documents.

Yet still, despite this last joined effort in 1995 and continued recruitment of new authors, the impression remains after 1992/1993 things went steeply downhill. The sparse documents show a network with less coordination

After some years of legal actions, in 1998, the US government reached the

Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement. More and more whistleblowers were explaining industry methods, the industry realized it would face trial long before 1998, and knew the authorities would be uncovering the lobbying-tactics and people used by the industry.

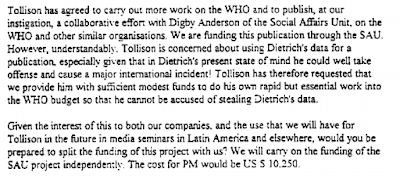

It is nearly impossible to find anything relevant to the economists network in the LTDL from 1995 onwards and the documents often stopped giving names. The first attempts to hide names started around 1995, until the 1998 Settlement, after which the industry systematically stopped using names. From that point on, it is impossible to trace the network. In 1995 Savarese and Tollison wrote another proposal for the Tobacco Institute though, proposing several studies, op-eds etc. Amongst the

proposals was a $27,500 report that would conclude that a Rand Corporation study in JAMA overestimated the social cost of tobacco. Of course, they knew their conclusion before actually conducting the research.

The early documents always carried the names of the economic consultants and overview of whose op-eds were published, but in 1998 James Savarese simply wrote "payment of $22,000 for "Consulting Services -

Op-Ed Project - 1st of 2 payments".

Unlike the documents from the 1980's the invoice does not mention a single name. While the document overviews the published op-eds, it does not mention the names of the authors, only the university where the op-ed was written. Only through the older documents is it still possible at times to link the university with the author. Yet it is clear the Savarese memo differed strongly from those from the 1980's. Remember the 1987 audit, and the industry complaining Savarese withheld some names from the industry? The industry was aware it was under scrutiny in and started culling names...

Even though the network of economic consultants vanished from the LTDL, it seems it did not really cease to exist, but rather the industry adapted communications to the new reality after the Tobacco Masters Settlement Agreement. Thus, it is not possible to detect if the network really ceased to exist or not. The correct title of this chapter therefore perhaps should have been: the end of the traceable network.

Yet another possible reason the industry stopped working with the economists is that it seems people like Tollison and Wagner became very radical, and started writing op-eds with titles like

Scientific integrity consumed by anti-smoking zealotry. DEspite this ectreme title, it was

cleared by the Tobacco Institute. The same year they wrote

a letter tot the editor, stating

In 1999, only a handful of the social consultants

signed an open letter to the US Attorney General, defending the tobacco industry. It contained the standard free-market reasoning, wans was signed by 5 network members (Bruce L. Benson, Robert B. Ekelund, Lowell Gallaway, William F. Shughart, II and Walter E. Williams) and some 37 other economists, all of them known for their strong free-market views. By that time (1999), the role of the economists network had already been replaced by tobacco-friendly think tanks, and this letter probably originated somewhere in a think tank, not the Tobacco Institute's economists network.